By Dave Johnson, P.E. and Dr. Chait Bhat, Ph.D., LCACP

Data-driven validation of pavement sustainability through well-maintained pavement management systems

A significant amount of funding is being provided to state, local and non-governmental road agencies

as part of the low-carbon transportation materials program in the United States1. This article highlights the need to efficiently maintain, update and use pavement management data to ensure low-carbon sustainable pavements over the whole life-cycle scope.

Previous articles in this column discussed how contracting mechanisms and project delivery methods can facilitate the validation of holistic sustainability. Similarly, this article discusses how a well-maintained and robust pavement management system (PMS) can be utilized to make data-driven sustainability decisions to meet all four pillars of pavement sustainability: performance, economic, environmental and social.

What are pavement management systems?

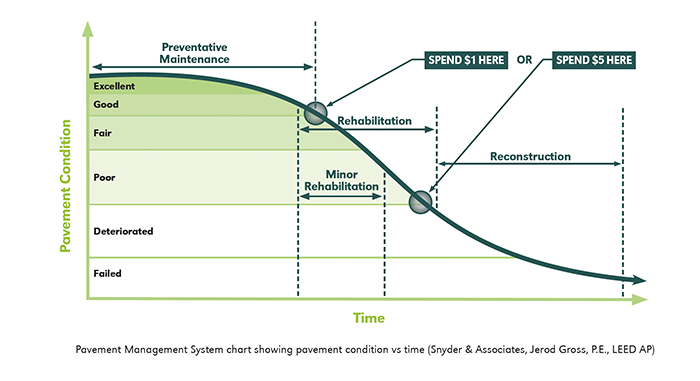

A PMS is a set of defined procedures for collecting, analyzing, maintaining and reporting pavement data, to assist the decision makers in finding optimum strategies for maintaining pavements

in serviceable condition over a given period for the least cost2. Typical “pavement data” consists of section numbers (typically marked within a mile), pavement surface type, materials, construction year, design, surface distresses such as cracking and rutting, structural deformations, maintenance treatments and other information. Imagine this system covering thousands of miles of pavement within an agency’s jurisdiction – lots of data, right? A PMS can be used for making design and procurement decisions based on historical performance, or for validating assumptions made around maintenance, life cycle assessment and cost analysis.

A brief history of pavement management systems

Pierre Marie Jerome Tresaguet may have been the founder of PMS in 17753. As the French Inspector General of Roads for King Louis XVI, he promoted an innovative design philosophy of a light surface

on a strong, well drained base. Most importantly as it relates to this discussion, he saw that continuous maintenance encouraged a longer life cycle and a higher level of service for users.

Now fast forward 200 years to the modern development of PMS that began in the 1960s and early 1970s.

Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT) has been widely recognized as a leading state in the use of PMS. They began a complete system inventory in the mid-1960s and started doing biannual system surveys in 1969, moving to annual surveys by 1988. WSDOT’s robust and well-maintained PMS was a critical resource when they were required by legislation in 1993 to select projects based on life-cycle cost analysis. The benefits of these efforts were evident when the percentage of the road system deemed to be in good condition increased from 50 percent in 1970 to 93.5 percent in 20054.

Other user agencies, notably Arizona, Florida, Ontario, Saskatchewan and Utah, were recognized PMS leaders as well. In 1977, Utah was credited with coining the phrase “Good Roads Cost Less.” In 1990, the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO) published “Guidelines for Pavement Management Systems.” In 1995 and again in 2017, AASHTO supported NCHRP Syntheses on PMS5.

The Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) took a leadership role with PMS in the 1990s. With the passing of the Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act (ISTEA) in 1991, Congress required each state highway administration to implement a PMS. Then in 1996 following the development of a Transportation Asset Management philosophy, FHWA organized an Executive Seminar on Asset Management.

Progress continued in the 2000s as FHWA published its first “Pavement Management Roadmap” in 2010

which was updated in 2022. In the 2022 version, a pavement management vision was offered as6:

“Pavement management supports agency investment decisions using quality data and analysis tools that encourage the consideration of long-term consequences on pavement and system performance in alignment with building safe, sustainable and equitable transportation systems.”

Consequently, there is an active movement for agencies to utilize their PM systems in ensuring the economic and environmental stewardship of their very large road assets.

PMS and pavement sustainability

Quantification and monitoring each of the four pillars over a pavement’s full life-cycle is crucial for validating sustainability. Currently, the practice of monitoring at least one pillar (e.g., performance) within a PMS varies across different state DOTs. This may be attributed to the varying amount of resources (such as funding and workforce) available within an agency to support their PMS. In addition, there are many instances where the PMS within an agency is managed by a team/division that is separated from the materials and design team. This can act as a hindrance to quantify and monitor sustainability aspects over the life-cycle of pavements both at the project and network levels.

State of practice for use of PMS to achieve pavement sustainability

An excellent publication to assess the latest state of practice on the use of PMS is the “2017 NCHRP Synthesis, Pavement Management Systems: Putting Data to Work.”5 Information was gathered from a literature review, a state/provincial agency survey and follow-up phone interviews with five of the responding agencies based on their communication of innovative uses of PMS data.

While significant progress in the PMS arena has occurred over the past 60 years, the synthesis noted several areas for improvement. Examples included:

• Only 20 of 48 agencies (or 42 percent) were reporting maintenance activities.

• Only 11 of 48 agencies (or 23 percent) had information on materials or construction.

• Only six of 48 agencies (or 13 percent) had detailed performance data.

To access influences on life-cycle performance of pavements, and thus the four pillars of sustainability, these data points are needed.

Performance modeling by agencies was much more common, as reported by 33 of 48 agencies (or 69 percent). The five most common variables reported for development of these models were pavement type, pavement functional condition, highway system, treatment history and traffic data. Interestingly, neither environmental sustainability nor safety data were used.

A global example of a well-funded, maintained and publicly accessible PMS system would be the PMS used in Sweden.

A plethora of data on road sections have been made available every year through the PMS for Swedish roads. Because of the abundance of data and the ease in accessibility, data-driven decision making is the norm at both the project level and the network level7. Increasingly, researchers are promoting ways to incorporate data that will evaluate the potential environmental effects such as greenhouse gas emissions of construction and maintenance activities.

The results of these Swedish research efforts highlight a positive correlation between a higher pavement condition score and lower environmental impacts over the life cycle of pavements8,9. In addition, insights from well-maintained and granular (i.e., intricate level of detail) PM systems show lower life cycle costs when maintaining high performance levels as compared to a traditional worst-case rehabilitation approach10.

Conclusions

There is a well-known quote about PMS which goes like, “A PMS does not make decisions, stakeholders do.” As with any other data source, the management and utilization of PMS is stakeholder specific. As new materials and construction techniques emerge within the pavement arena, PMSs will play a crucial role in determining overall sustainability of pavement systems. Sufficient funding and an adequate workforce are required to maintain an efficient PMS that will support pavement sustainability by providing a feedback loop between procurement systems, design systems, project management databases and PMS.

References

1. Low Carbon Transportation Materials Grants Program. United States Department of Transportation. fhwa.dot.gov/lowcarbon/

2. Vitillo, Dr. Nick. Pavement Management Systems Overview – www.nj.gov

3. Haas, R.C.G., Hudson, W.R. and Zaniewski, J.P. (1994) Modern Pavement Management. Malabar, Fla: Krieger Pub. Co.

4. Pavement Design & Management (2024) WSDOT wsdot.wa.gov

5. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2017. Pavement Management Systems: Putting Data to Work. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi.org/10.17226/24682

6. Zimmerman, K et al., (2022). Pavement Management Roadmap. Federal Highway Administration. Report No: FHWA-HIF-22-054. fhwa.dot. gov

7. Eklöf, K. (2018) Report: Long-term effects of an underfunded road maintenance budget. kristin.salbo.ai/portfolio/

8. France-Mensah, J., and O’Brien, W.J. (2019) ‘Developing a sustainable pavement management plan: Tradeoffs in road condition, user costs, and greenhouse gas emissions’, Journal of Management in Engineering

9. Del Campo Yañez, J.M., Lee, M.M. and Swei, O. (2023) ‘Sustainable Infrastructure is a two-way street: Balancing Environmental and condition performance goals’, Journal of Management in Engineering

10. France-Mensah, J., and O’Brien, W.J. (2018) ‘Budget allocation models for pavement maintenance and Rehabilitation: Comparative Case Study’, Journal of Management in Engineering